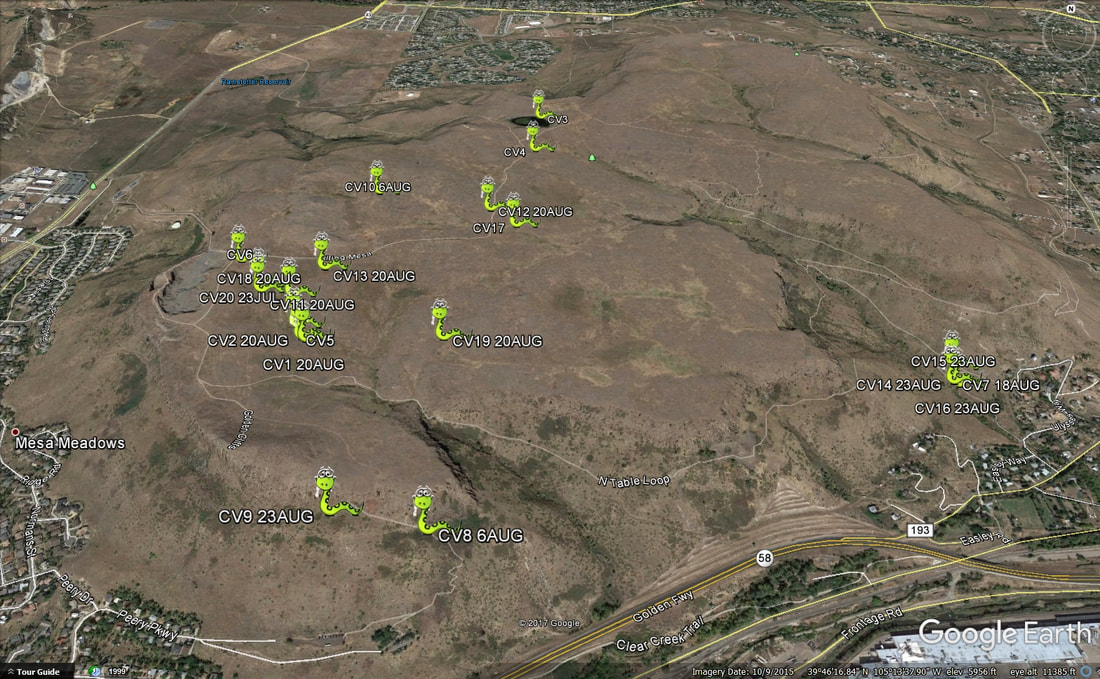

Updated Map

|

By Bryon Shipley I often wonder if our rattlesnakes will soon grow tired of seeing/smelling us snake signal trackers as we lean into their personal space to record their current locations on the mountain week after week. On the other hand, we are always excited to see what our snake friends are up to from week to week, carefully checking their health status visually, admiring their coloration, and being amazed at how well their camouflage works. It is remarkable that despite our frequent visitations, the rattlesnakes are seemingly very tolerant, hardly reacting to our presence, even when we find them cruising through tall grass on their way to keeping whatever appointment they have for the day. The big news is that we discovered new babies with female number 9, who is located at the Golden Cliffs. We could not count the number of babies, but it was fantastic to see the new generation about to make their mark on the planet! And they were right on time, as we have noticed with other rattlesnake populations, mid-August being the preferred beginning of the birthing time. We are hoping that a few of our other females will be birthing very soon as well. Coincidentally, the boy snakes are making their pitch to find that alluring female somewhere out in the grassland in hopes of creating more babies---it’s a busy time of year! Some studies indicate that perhaps only 50-55% of babies survive their first hibernation, and females in some populations don’t breed until their 3rd year, and then only every other year or every two years. It’s a real challenge keeping up with nature’s demands. Can you see mom and babies in this photo? Hint: look at bottom edge of rock formation! Recently, it’s been perplexing tracking these rattlesnakes, as some transmitter signals disappear for a time and others resurface. It’s possible some snakes that we haven’t found in a long time have met their destiny with a predator, which includes hawks, owls, ravens, badgers, coyotes, racer snakes, and milksnakes, but we never know for sure what to expect. For example, if snakes go into a shedding cycle, they could be underground for 10 days until they shed their skin; places where transmitter signals don’t always surface. Similarly, after a snake has a meal, he might decide to sit tight and digest the meal underground for quite a while (rattlesnakes are amazing efficient digesters and can subsist on 2-3 meals a year if necessary). All this means is that snake signals are not easy to detect at certain times.

Most of the snake group east of the quarry are adhering to a tight home range, while the snake group at the middle of the mountain top is somewhat scattered, one big male apparently enjoying the cool, humid confines of burrows that prairie dogs provide. In another location on the south side of the mountain, there is quite a neighborhood of sociable rattlesnakes, mostly females that are sharing a particular rock crack with each other, occasionally trading off with another individual from a different nearby neighborhood. This particular rock must be special for these snakes, probably providing great security from predators and protection from excessive heat, but also supplying just the right temperature opportunities for developing babies (rattlesnakes give birth to live young) without too much exposure to predators. This rock seems special for socializing and aggregating, a behavior well-studied in Timber rattlesnakes in the northeast United States, but not so much with Prairie rattlesnakes. Speaking of sociable snakes, we have discovered several instances where different species of snakes have been utilizing the protection of certain rock cavities. The species using the same rocks have been identified by the shed skins they left behind and include rattlesnakes, bullsnakes, and racer snakes. Probably, they were using these retreats in the rocks at different times, but also possibly at the same time. It’s amazing to find intriguing evidence of animal associations when it is commonly thought that rattlesnakes would never share living space with other snakes! Ain’t nature grand? |

AuthorJoseph Ehrenberger Archives

October 2017

Categories |